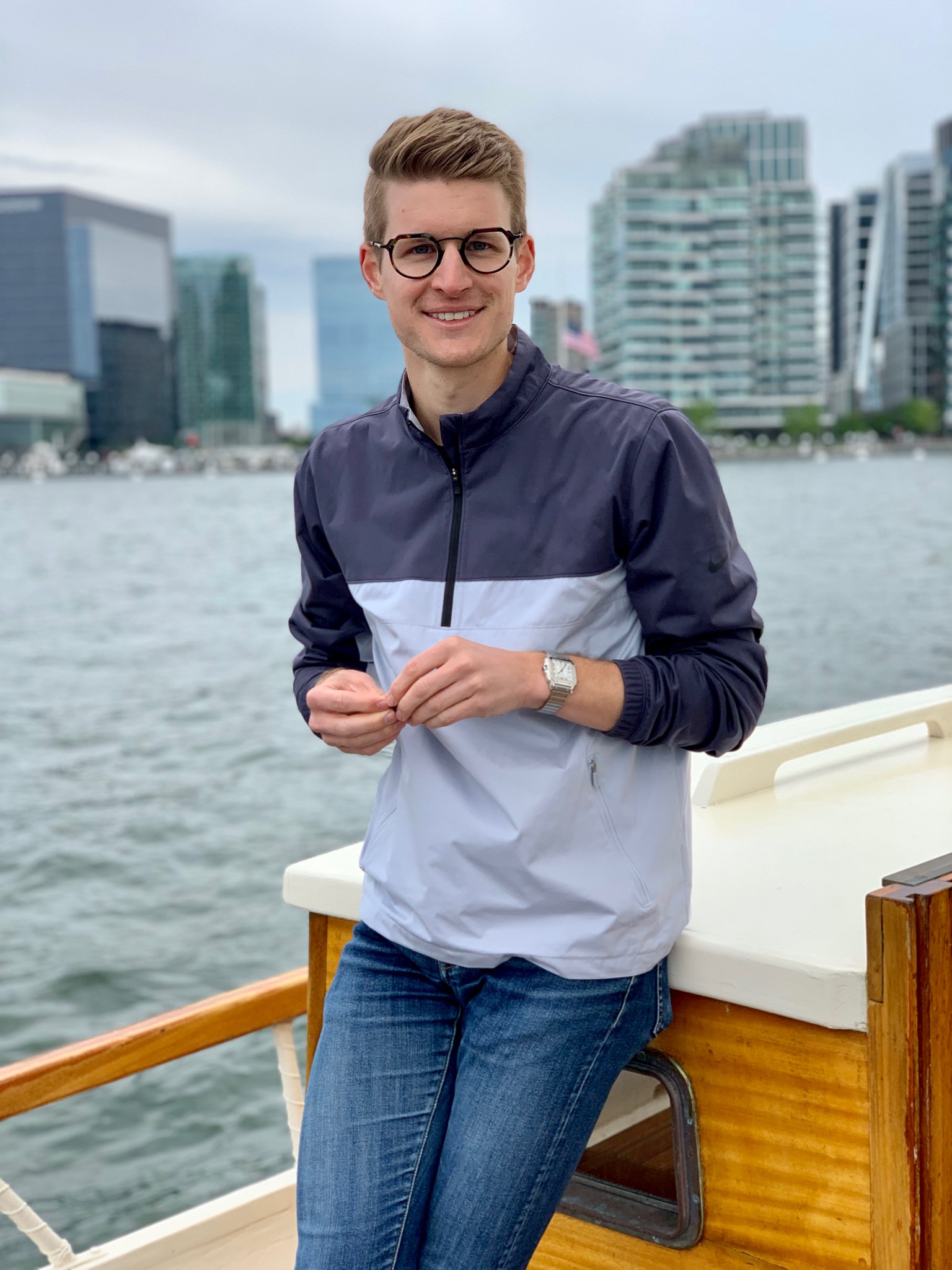

In this edition of DRRN Member Highlights, we’re featuring Ethan Raker, an Assistant Professor of Sociology at the University of British Columbia. As a social demographer specializing in disasters, Ethan’s research examines the health and population consequences of extreme weather events, with a focus on racial and socioeconomic disparities. Read on to learn more about his work and insights!

Could you introduce yourself and tell us about your current research?

Hello! I’m an Assistant Professor of Sociology at UBC and a social demographer specializing in disaster research. My work focuses on understanding the health and population consequences of extreme weather-related disasters, particularly how these events disproportionately affect different racial and socioeconomic groups.

To achieve this, I integrate diverse data sources—including administrative records, censuses, geospatial weather data, and health surveys—and analyze them using quantitative methods. My work includes studies on the effects of severe tornadoes on neighborhood-level population demographics and infant health outcomes. I’ve also undertaken projects examining specific disaster cases, such as Hurricane Harvey in Houston, Texas, and Hurricane Katrina in New Orleans, Louisiana. My ongoing research focuses on extreme heat, including studies on mortality outcomes and fertility patterns across the United States and British Columbia, Canada.

What motivated you to become a part of the DRRN community?

I joined the DRRN community to connect with scholars across campus who focus on similar topics. Having trained in interdisciplinary research settings, I deeply value the intellectual and political benefits of bringing diverse perspectives to the study of disasters. The DRRN community offers opportunities for collaboration, engagement with policymakers in the province, and support for graduate students and postdocs I might not have otherwise encountered.

What do you wish practitioners or policymakers would ask you about your research? What insights would you like to share with them?

I’ll use my recent project on Hurricane Harvey as an example, which resulted in three papers on mental health outcomes. In one published paper, my collaborator Kevin Smiley (LSU) and I found that the mental health effects of disasters were greater in neighborhoods with lower levels of social capital (i.e., the resources, connections, and trust embedded in social relationships). For policymakers aiming to reduce the mental health burden of extreme weather events, this suggests that investments in policies and programs to strengthen neighborhood networks—such as community development initiatives, volunteer programs, leadership training, and community support groups—could help improve population health during disasters.

In a second, published paper, I demonstrate that the mental health impacts of severe flooding were worse for people living outside federally designated floodplains compared to those within these zones. This finding highlights the importance of extending public messaging and risk awareness beyond traditional spatial boundaries of vulnerability, especially as climate change exacerbates the severity of floods, affecting communities previously considered safe.